On the border between hipster and Hasidic, a Brooklyn barbershop specializes in Orthodox haircuts

For the Bukharian Jewish barbers on Williamsburg’s Kent Avenue, payot are no problem

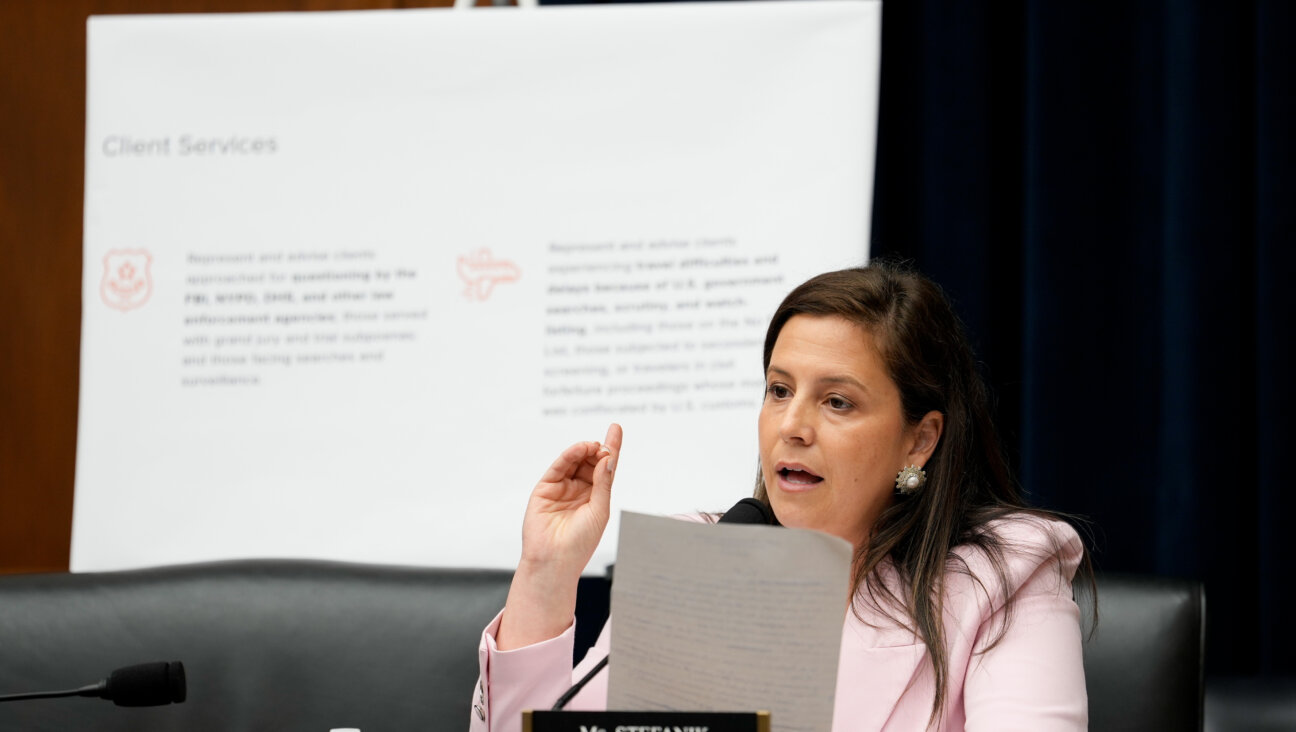

At Kent Avenue Barber Shop, Gabi Zav attends to a customer. Photo by Jacob Hersko

At Kent Avenue Barber Shop in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, barbers have different strategies to make sure they don’t accidentally cut off their customers’ payot, the curly sidelocks that help give Hasidic men and boys a distinct appearance.

One barber uses a velcro gripper to secure the payos to the tops of Hasidic men’s heads while he cuts the rest of their hair. Another barber twirls the payot around his finger and moves them to the front of the face.

“When you tell people you work in Williamsburg, they ask one of two questions,” said Ray, a barber who declined to share his last name. “‘With all the Hasidic people,’ or ‘with all the hipsters?’”

Here, just a block south of the Williamsburg Bridge, near the dividing line between those two polar opposite Williamsburgs, the answer is “both.” Outside the barber shop’s window, there’s a healthy flow of shirtless joggers and Hasidic moms pushing strollers.

Inside, four barbers — all Bukharian Jews — speak to each other in Hebrew and offer customers fancy armchairs, whiskey and, for the teetotalers, water and soda, as pop music plays on the radio. A haircut here costs anywhere from $20 for a shape-up to $100 for a haircut and a hot towel shave.

Hasidim who come here include singers and businessmen — people whose careers encourage them to pay extra attention to their appearance. Although these people are generally less sheltered from the secular world than full-time rabbis or teachers, their interactions with Bukharian barbers still bring out the unique qualities of each group, and how they perceive each other as Jews.

Owner Gabi Zav, an immigrant by way of Tajikistan and Israel, first opened the barber shop in 2021 and asked Ray — his cousin — to join him. It took a while to earn Hasidic customers’ trust.

“For them, because we don’t wear the kippah and we don’t have payos, we’re not Jewish,” Zav said. He recalled an interaction with a Hasidic customer who couldn’t see why the barber shop was closed on Saturdays. “‘Oh, why you’re not working Shabbat?’ ‘Because I’m Jewish.’ ‘How are you Jewish?’”

Dovy Meisels, a Hasidic singer who comes to Kent Avenue Barber Shop before his performances, is more open-minded than some of Zav’s other customers. “I don’t see a Bukharian, I don’t see a Syrian, I don’t see a Modern, I don’t see a Litvack, I don’t see a chusid,” he said. “I see a holy Jew, and a holy soul, and that’s what I love.”

Like many Hasidic men, Meisels used to get his hair cut in the mikveh, or ritual bath house, where it’s done quickly for about $10.

“There’s lots of people. Everyone gets two minutes,” Meisels said of the mikveh. “Someone who goes to events, or anyone who wants a nice job, comes to a professional place.”

Meisels has a trimmed beard and wears his payot high; the neat, tight curls begin almost as high as his kippah and extend almost up to his chin. The back of his head has what barbers call a natural fade.

When someone like him goes to this barber shop, he’s not just entrusting the barbers with his hair. Payot are how Hasidic men signal to themselves and the rest of the world their strict religious devotion — for them, to entrust a barber with your payot is to entrust him with a piece of your identity.

The professional barbers at Kent Avenue Barber Shop have earned that trust. Bukharians are ubiquitous in New York City barber shops, and many view haircutting not just as a gig, but as a craft.

In the Soviet Union, Zav’s father attended an elite college and became a mechanical engineer. His degree and experience meant little in Israel and the U.S., though, and the father — like others who benefited from the industry’s low barriers to entry — became a barber. Zav followed his lead.

Ray, who is also an Israeli immigrant, is no stranger to navigating complex cultural dynamics in the barber shop. His parents named him Rahmin, but in the U.S., his name kept getting mispronounced, and he didn’t want to attract his customers’ attention to his ethnicity. First he became Ronny, then Ron. That lasted until he started working at a barber shop where there was already a Ron. “They’re like, ‘oh, if you want, you can be Ron Junior.’ I’m like, ‘I’m like twice the size of this guy, what’s Ron Junior?’” So he became Ray instead.

Another time, he worked at a barber shop near Coney Island, where he made the mistake of letting a Syrian Jewish boy trick him into cutting his hair too short. The haircut drew ire from a wide range of sources. “The rabbi called, the mom called, the father called, someone else from the synagogue called, and they’re like, ‘yo, what did you do?’”

Ever since then, Ray treads lightly when cutting Haredi hair. If a Hasidic customer asks for an edgy hairstyle, he gives him a stern warning before complying. Zav does the same.

“I explain to them, this is a haircut for the goyim,” Zav said. “If you’re OK, we’re going to do it, but don’t complain or put on Google a bad review.”